Life on the inside: Human rights in Canada’s prisons

Investigating Canada’s prisons

The Senate Committee on Human Rights is studying the human rights of prisoners in the federal correctional system to investigate access to mental health treatment, the effect of segregation and the overrepresentation of minorities in prisons, among other topics.

On a fact-finding mission between May 15 and May 19, 2017, committee members got inside access to:

- Brockville Mental Health Centre (Brockville, Ont.)

- Joyceville Institution and neighbouring Pittsburgh Institution (near Kingston, Ont.)

- Millhaven Institution and neighbouring Bath Institution (Bath, Ont.)

- Collins Bay Institution (Kingston, Ont.)

- Joliette Institution for Women (Joliette, Que.)

- Waseskun Healing Lodge (Saint-Alphonse-Rodriguez, Que.)

- Regional Reception Centre (Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines, Que.)

On television, prison is almost formulaically grim.

There is violence and sadism, moral victories and crippling setbacks, abusive guards and volatile inmates all packed together in a claustrophobic maze of iron and concrete.

Members of the Senate Committee on Human Rights sought to pierce the pop culture perception of prisons as part of a sweeping study of the federal correctional system and the human rights of prisoners.

Prisoners at Joliette Institution make underwear for male prisoners in other federal penitentiaries.

To that end, committee chair Senator Jim Munson and Senators Kim Pate, Marilou McPhedran and Nancy Hartling were granted rare access to some of Canada’s most secure penitentiaries during a fact-finding mission to the Brockville, Kingston and Montreal areas.

The average, ordinary, everyday life of prisoners is a dreary parade of petty indignities, the committee heard.

At Joliette women’s prison near Montreal — where the majority of women have histories of physical and sexual abuse, the only available work is sewing underwear for men held in other federal institutions.

Payment, as with all federal prison jobs, tops out at $6.90 per day.

The money is supposed to help prisoners develop a small amount of savings that they can use to help them build a life on the outside.

But the federal government claws back 30% to contribute toward for room and board, and to defray administrative expenses like phone services, even though prisoners must pay for each phone call they make.

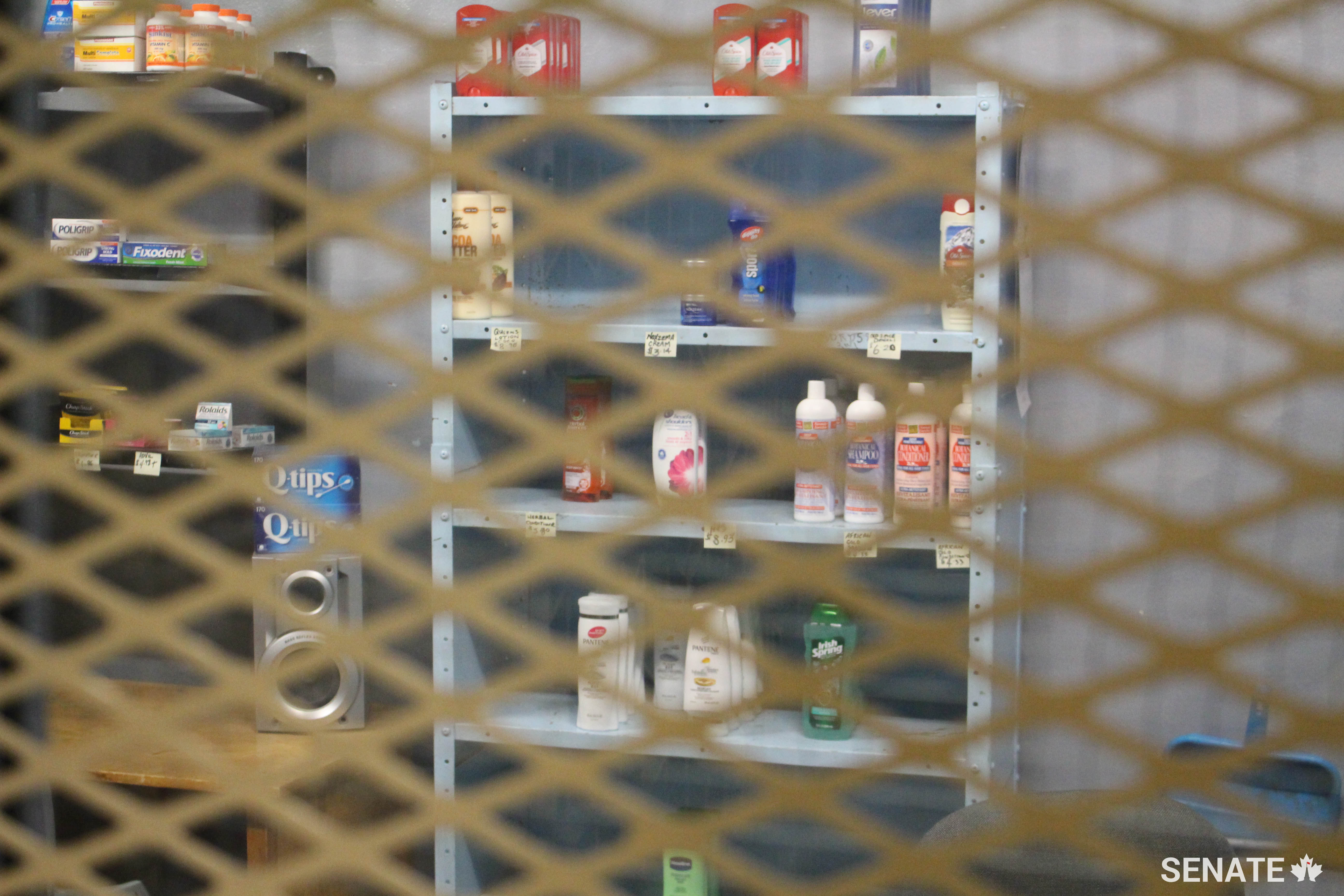

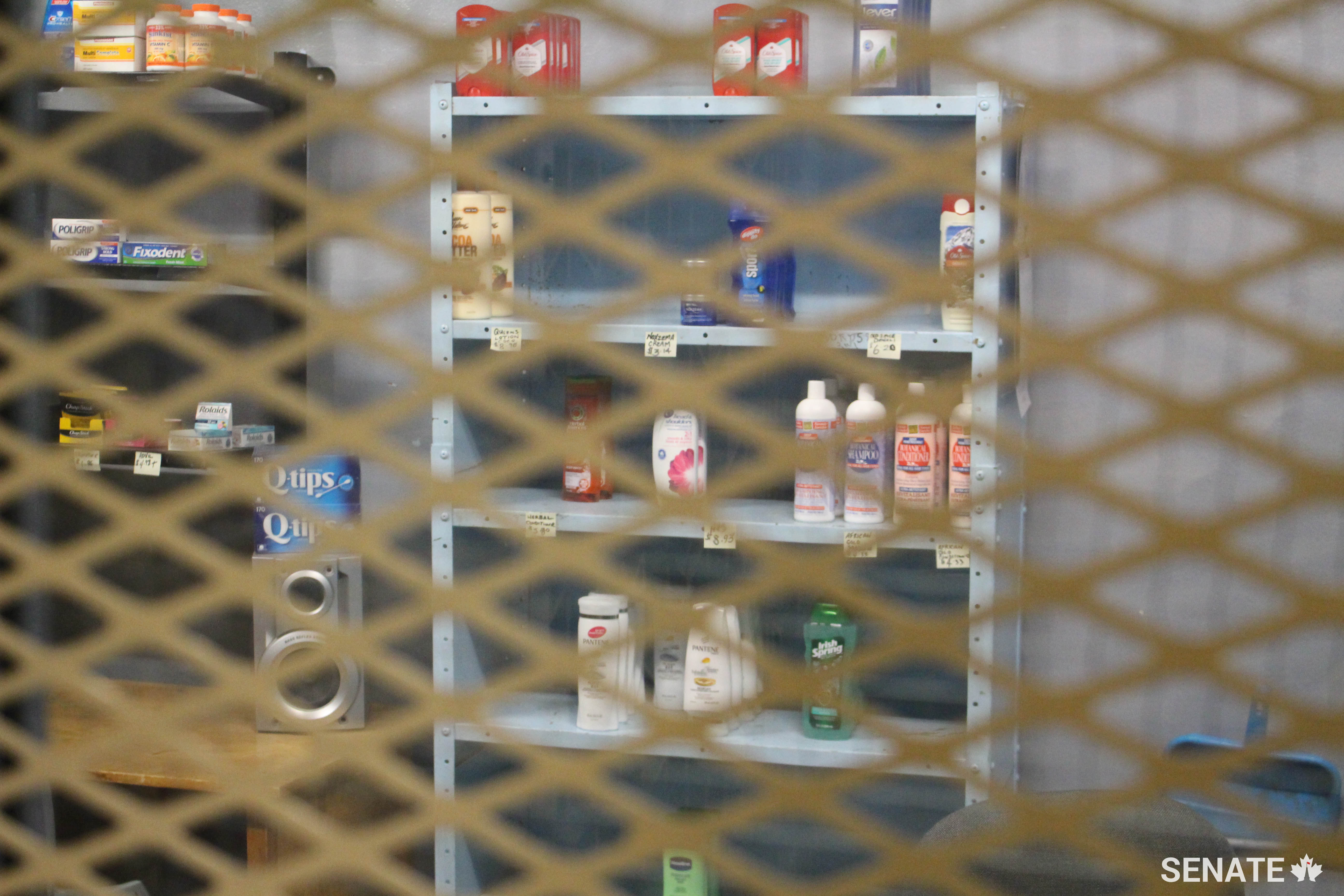

And in practice, a lot of this money goes right back to the prison via the canteen — small tuck shops where prisoners can by things like pharmacy items and food.

The women of Joliette are only given one type of sanitary pad; tampons and even incontinence wear that older prisoners may require must be bought and paid for from their canteen fund.

It’s a similar story with food.

On the Ontario side, prisoners of the Bath Institution prepare meals for area prisons from a large industrial kitchen.

Senators heard the food is widely panned by prisoners, leading prisoners to rely more and more on canteens for food because of the inadequacy of mass-produced meals.

Upon release, each prisoner is guaranteed to leave with $50 and that’s often all they’re left with.

To make matters worse, prisoners on statutory release — it is not uncommon for prisoners to be let back into the community under supervision after serving two-thirds of their sentence so they can reintegrate into society while still under institutional supervision — sometimes don’t even know where they will be heading until the day they are released.

Committee chair Senator Jim Munson and Senators Kim Pate, Marilou McPhedran and Nancy Hartling spoke extensively with prisoners and staff at penitentiaries in Ontario and Quebec during a May 2017 fact-finding mission.

One prisoner, the committee heard, had planned to go to the Toronto area where he had supportive family. Instead, the day of his release, he learned he would go to Windsor, Ont., where he knew no one.

Some prisoners nevertheless expressed gratitude for their time on the inside. At Waseskun Healing Lodge, a gateless facility for minimum-security Indigenous prisoners, one man said he was happy he’d been able to reconnect with his heritage.

Senators expressed appreciation for his perspective but underscored the reality that it is an indictment of the historical oppression of Indigenous peoples that so many have been dislocated from their lands, culture and language.

Senators also suggested that better social programming in the first place could have spared him from crime and a federal prison sentence.

This is only the beginning of the study; the committee hopes to make a preliminary set of observations on the human rights of prisoners in the fall.

Related articles

Tags

Committee news

Life on the inside: Human rights in Canada’s prisons

Investigating Canada’s prisons

The Senate Committee on Human Rights is studying the human rights of prisoners in the federal correctional system to investigate access to mental health treatment, the effect of segregation and the overrepresentation of minorities in prisons, among other topics.

On a fact-finding mission between May 15 and May 19, 2017, committee members got inside access to:

- Brockville Mental Health Centre (Brockville, Ont.)

- Joyceville Institution and neighbouring Pittsburgh Institution (near Kingston, Ont.)

- Millhaven Institution and neighbouring Bath Institution (Bath, Ont.)

- Collins Bay Institution (Kingston, Ont.)

- Joliette Institution for Women (Joliette, Que.)

- Waseskun Healing Lodge (Saint-Alphonse-Rodriguez, Que.)

- Regional Reception Centre (Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines, Que.)

On television, prison is almost formulaically grim.

There is violence and sadism, moral victories and crippling setbacks, abusive guards and volatile inmates all packed together in a claustrophobic maze of iron and concrete.

Members of the Senate Committee on Human Rights sought to pierce the pop culture perception of prisons as part of a sweeping study of the federal correctional system and the human rights of prisoners.

Prisoners at Joliette Institution make underwear for male prisoners in other federal penitentiaries.

To that end, committee chair Senator Jim Munson and Senators Kim Pate, Marilou McPhedran and Nancy Hartling were granted rare access to some of Canada’s most secure penitentiaries during a fact-finding mission to the Brockville, Kingston and Montreal areas.

The average, ordinary, everyday life of prisoners is a dreary parade of petty indignities, the committee heard.

At Joliette women’s prison near Montreal — where the majority of women have histories of physical and sexual abuse, the only available work is sewing underwear for men held in other federal institutions.

Payment, as with all federal prison jobs, tops out at $6.90 per day.

The money is supposed to help prisoners develop a small amount of savings that they can use to help them build a life on the outside.

But the federal government claws back 30% to contribute toward for room and board, and to defray administrative expenses like phone services, even though prisoners must pay for each phone call they make.

And in practice, a lot of this money goes right back to the prison via the canteen — small tuck shops where prisoners can by things like pharmacy items and food.

The women of Joliette are only given one type of sanitary pad; tampons and even incontinence wear that older prisoners may require must be bought and paid for from their canteen fund.

It’s a similar story with food.

On the Ontario side, prisoners of the Bath Institution prepare meals for area prisons from a large industrial kitchen.

Senators heard the food is widely panned by prisoners, leading prisoners to rely more and more on canteens for food because of the inadequacy of mass-produced meals.

Upon release, each prisoner is guaranteed to leave with $50 and that’s often all they’re left with.

To make matters worse, prisoners on statutory release — it is not uncommon for prisoners to be let back into the community under supervision after serving two-thirds of their sentence so they can reintegrate into society while still under institutional supervision — sometimes don’t even know where they will be heading until the day they are released.

Committee chair Senator Jim Munson and Senators Kim Pate, Marilou McPhedran and Nancy Hartling spoke extensively with prisoners and staff at penitentiaries in Ontario and Quebec during a May 2017 fact-finding mission.

One prisoner, the committee heard, had planned to go to the Toronto area where he had supportive family. Instead, the day of his release, he learned he would go to Windsor, Ont., where he knew no one.

Some prisoners nevertheless expressed gratitude for their time on the inside. At Waseskun Healing Lodge, a gateless facility for minimum-security Indigenous prisoners, one man said he was happy he’d been able to reconnect with his heritage.

Senators expressed appreciation for his perspective but underscored the reality that it is an indictment of the historical oppression of Indigenous peoples that so many have been dislocated from their lands, culture and language.

Senators also suggested that better social programming in the first place could have spared him from crime and a federal prison sentence.

This is only the beginning of the study; the committee hopes to make a preliminary set of observations on the human rights of prisoners in the fall.