When the tyrant is in the house: Senator McCallum

Tags

The man was strapped to the large wheel that continued to turn endlessly. At the base of the cycle the sharp points of metal, which were anchored to the ground, tore into his stomach. At the peak of the cycle salt was poured into his wounds. The flames of the fire threw great heat in the labyrinth and roared closely to the wheel. As the wheel reached ground level the pitcher of water was just outside his reach and the heat was unbearable and so his thirst was even more unbearable.

— Mary Jane McCallum, ‘Bless Me Father for I Have Sinned’ from First Lady Nation, Volume II: Stories by Aboriginal Women, edited by Linda Ellis Eastman

This image of hell that I, as a small child, envisioned while I was at the Guy Hill Catholic residential school won me first prize in religion class. The fear of hell has remained with me throughout my life; today I still believe I will end up in hell.

Why?

Because Sir John A. Macdonald believed, and had the power to make other settlers believe, that we were savages; less than human. He made me believe it as well — for a time. I also believed that he represented the civilized. Looking at the state of the world today, is this civilization?

Through the land-based education I received as a little girl in the trapline and fish camp, as well as the teachings of connection; relationship; spirituality and purpose in life, I was solid. As Bob Seger wrote, “My eyes were clear and bright, my life had purpose, my steps were quick and light and I held firm with what I knew was right.” Yet at the age of five, I fell victim to the hustlers and was sentenced to residential school where I had my identity reshaped to one based on shame, dependence, blind obedience and fear.

Sixty-nine years later, I am still on my reconciliation journey towards that child who first entered residential school. That little girl was already a success story and was not defective — that was my reality and my truth.

When people ask me today, “Why are we still having this conversation when this happened over 100 years ago,” I say: “I never met John A. Macdonald but I have been actively forced to follow his policy and law from birth until today. So have my children and grandchildren. And so have yours.”

Whether or not Canadians realize it, we are all colonized. The choice we have is whether we continue to be colonizers.

The second question we get asked is, “Why don’t you move on?”

If you were violently and without cause moved from where you are today, with no power to counteract, how would you move on?

If you were violently and relentlessly attacked as a child — physically, sexually, mentally, emotionally, spiritually and psychologically — by strangers who were supposed to protect you and were “closest to God,” how you would move on?

When you have witnessed deaths at the hands of God’s servants in this “civilized” world, how would you move on?

When life then becomes a performance according to these standards, according to a God they have created in their own image — hard, cold and inflexible — how would you move on?

I’m awaiting your advice.

Was residential school genocide or persecution? The trauma it created for me and others shattered the meaning of our lives and left death, disorder, disconnection and disempowerment.

Yet we will continue to tell our stories to recreate our sense of meaning and identity as we once knew them, as individuals and communities.

That is to reconcile.

The woman held the baby, wrapped in a blanket, and sat in a chair. The chair sat on top of a shiny, smooth, black rock, surrounded by water, and in a black cavern. There was complete blackness, but a light shone on the woman and child. All around the rock were four-legged slimy grey creatures that were looking hungrily at the child. They would attempt to slither closer to the woman and child. The woman leaned toward the creatures and said, “You are not going to get this baby.” She threw out as much love as she could, from her heart and spirit, and the creatures backed away. In her dream she realized “Love is the most powerful weapon...”

— Mary Jane McCallum, ‘Bless me Father for I have Sinned’

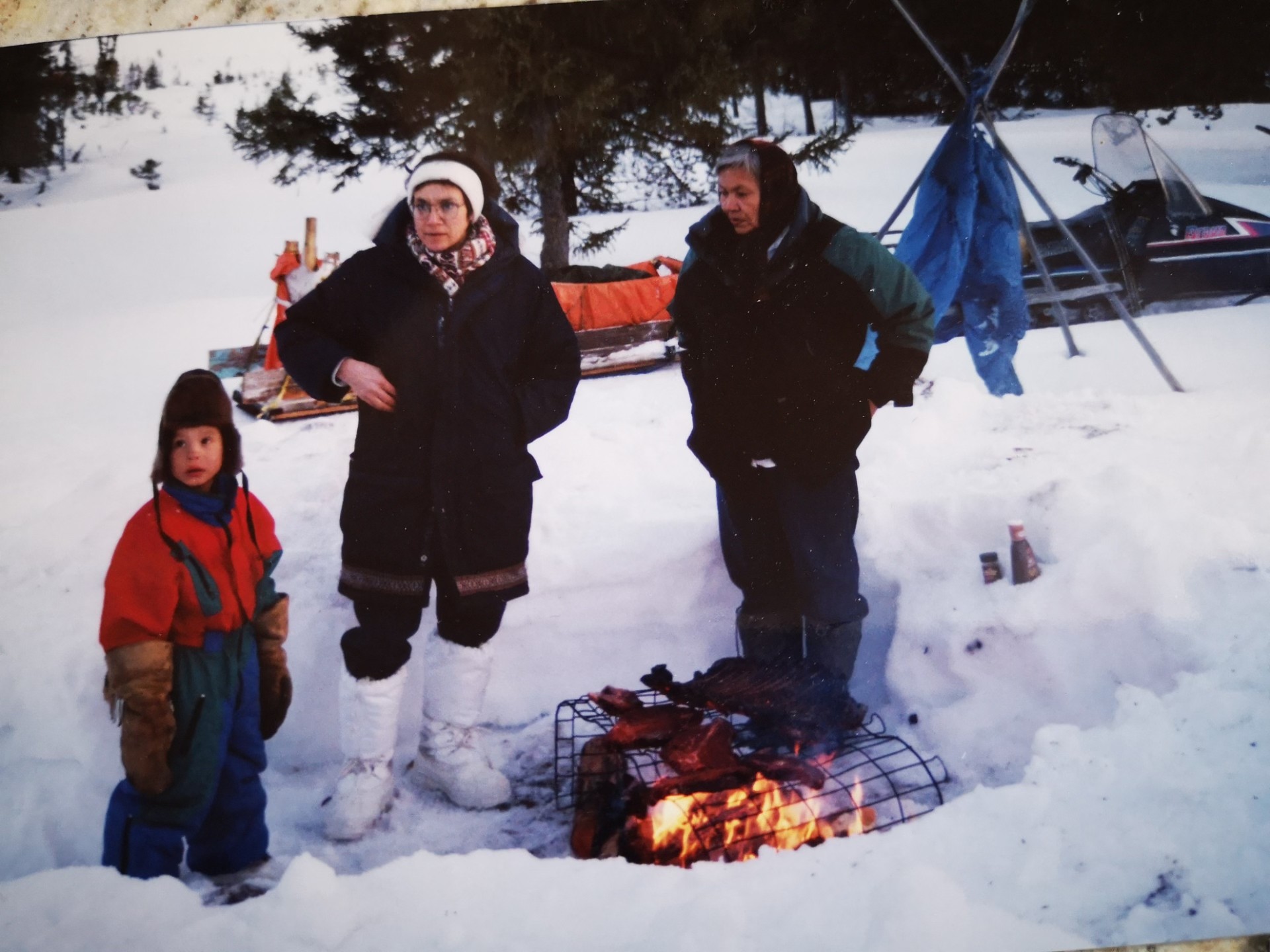

As a child, Senator McCallum, second from the right, won first prize in her religion class for her vivid description of hell. “The fear of hell has remained with me throughout my life,” she writes.

Well before she turned 16, Senator Mary Jane McCallum had been made to believe in residential school that she was less than human.

Senator McCallum, centre, holds an eagle feather as she is sworn in to the Senate. Despite everything she has accomplished, she is still scarred from her experiences at the Guy Hill residential school.

Senator McCallum looks up from a patient in this photo from 1978, when she was a dental nurse.

Senator McCallum graduates with a dentistry degree in 1990.

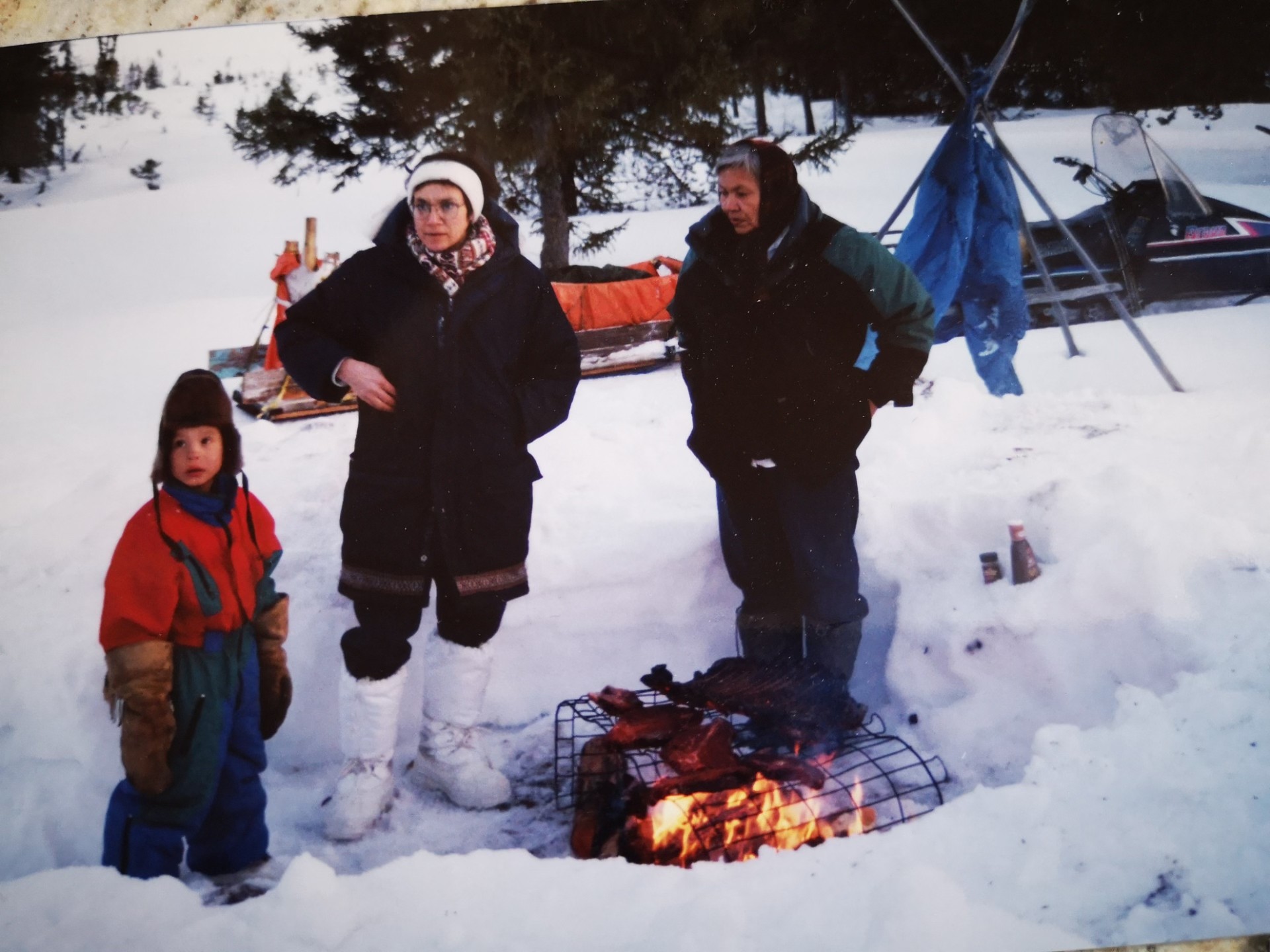

Senator McCallum’s dental practice took her to Indigenous communities across Manitoba, including her home reserve of Barren Lands First Nation.

Senator Mary Jane McCallum is a First Nations woman of Cree heritage who has provided dental care to First Nations communities across Manitoba during her long and distinguished career.

About the photos

The pictures you see are a journey of reconciliation of my identity, culture and community.

The first picture shows my forced assimilation within residential school. The second is me at age 16 in high school where I continued in western education. The photo of me practising as a dental nurse is when I began to view my work as providing a public service as opposed to viewing it strictly as a business. This is where my viewpoint began to turn towards decolonizing my way of thinking and my way of acting.

This strive towards decolonization intensified as I forged my path in dentistry, all the while continuing to challenge the market-based economy approach of health provision in favour of one that was more patient-centric.

The photo of me in my home reserve is emblematic of my continued reconciliation with both the land as well as community. This process of reconciliation and decolonization is still ongoing as I continue to bring voice to First Nations concerns in the Senate of Canada.

The man was strapped to the large wheel that continued to turn endlessly. At the base of the cycle the sharp points of metal, which were anchored to the ground, tore into his stomach. At the peak of the cycle salt was poured into his wounds. The flames of the fire threw great heat in the labyrinth and roared closely to the wheel. As the wheel reached ground level the pitcher of water was just outside his reach and the heat was unbearable and so his thirst was even more unbearable.

— Mary Jane McCallum, ‘Bless Me Father for I Have Sinned’ from First Lady Nation, Volume II: Stories by Aboriginal Women, edited by Linda Ellis Eastman

This image of hell that I, as a small child, envisioned while I was at the Guy Hill Catholic residential school won me first prize in religion class. The fear of hell has remained with me throughout my life; today I still believe I will end up in hell.

Why?

Because Sir John A. Macdonald believed, and had the power to make other settlers believe, that we were savages; less than human. He made me believe it as well — for a time. I also believed that he represented the civilized. Looking at the state of the world today, is this civilization?

Through the land-based education I received as a little girl in the trapline and fish camp, as well as the teachings of connection; relationship; spirituality and purpose in life, I was solid. As Bob Seger wrote, “My eyes were clear and bright, my life had purpose, my steps were quick and light and I held firm with what I knew was right.” Yet at the age of five, I fell victim to the hustlers and was sentenced to residential school where I had my identity reshaped to one based on shame, dependence, blind obedience and fear.

Sixty-nine years later, I am still on my reconciliation journey towards that child who first entered residential school. That little girl was already a success story and was not defective — that was my reality and my truth.

When people ask me today, “Why are we still having this conversation when this happened over 100 years ago,” I say: “I never met John A. Macdonald but I have been actively forced to follow his policy and law from birth until today. So have my children and grandchildren. And so have yours.”

Whether or not Canadians realize it, we are all colonized. The choice we have is whether we continue to be colonizers.

The second question we get asked is, “Why don’t you move on?”

If you were violently and without cause moved from where you are today, with no power to counteract, how would you move on?

If you were violently and relentlessly attacked as a child — physically, sexually, mentally, emotionally, spiritually and psychologically — by strangers who were supposed to protect you and were “closest to God,” how you would move on?

When you have witnessed deaths at the hands of God’s servants in this “civilized” world, how would you move on?

When life then becomes a performance according to these standards, according to a God they have created in their own image — hard, cold and inflexible — how would you move on?

I’m awaiting your advice.

Was residential school genocide or persecution? The trauma it created for me and others shattered the meaning of our lives and left death, disorder, disconnection and disempowerment.

Yet we will continue to tell our stories to recreate our sense of meaning and identity as we once knew them, as individuals and communities.

That is to reconcile.

The woman held the baby, wrapped in a blanket, and sat in a chair. The chair sat on top of a shiny, smooth, black rock, surrounded by water, and in a black cavern. There was complete blackness, but a light shone on the woman and child. All around the rock were four-legged slimy grey creatures that were looking hungrily at the child. They would attempt to slither closer to the woman and child. The woman leaned toward the creatures and said, “You are not going to get this baby.” She threw out as much love as she could, from her heart and spirit, and the creatures backed away. In her dream she realized “Love is the most powerful weapon...”

— Mary Jane McCallum, ‘Bless me Father for I have Sinned’

As a child, Senator McCallum, second from the right, won first prize in her religion class for her vivid description of hell. “The fear of hell has remained with me throughout my life,” she writes.

Well before she turned 16, Senator Mary Jane McCallum had been made to believe in residential school that she was less than human.

Senator McCallum, centre, holds an eagle feather as she is sworn in to the Senate. Despite everything she has accomplished, she is still scarred from her experiences at the Guy Hill residential school.

Senator McCallum looks up from a patient in this photo from 1978, when she was a dental nurse.

Senator McCallum graduates with a dentistry degree in 1990.

Senator McCallum’s dental practice took her to Indigenous communities across Manitoba, including her home reserve of Barren Lands First Nation.

Senator Mary Jane McCallum is a First Nations woman of Cree heritage who has provided dental care to First Nations communities across Manitoba during her long and distinguished career.

About the photos

The pictures you see are a journey of reconciliation of my identity, culture and community.

The first picture shows my forced assimilation within residential school. The second is me at age 16 in high school where I continued in western education. The photo of me practising as a dental nurse is when I began to view my work as providing a public service as opposed to viewing it strictly as a business. This is where my viewpoint began to turn towards decolonizing my way of thinking and my way of acting.

This strive towards decolonization intensified as I forged my path in dentistry, all the while continuing to challenge the market-based economy approach of health provision in favour of one that was more patient-centric.

The photo of me in my home reserve is emblematic of my continued reconciliation with both the land as well as community. This process of reconciliation and decolonization is still ongoing as I continue to bring voice to First Nations concerns in the Senate of Canada.