Anti-Black Racism

Inquiry—Debate Continued

November 1, 2018

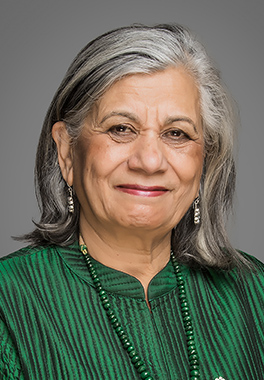

The Honorable Senator Ratna Omidvar:

Honourable senators, I rise today to speak to Senator Bernard’s very timely inquiry on anti-Black racism in this country. I want to thank Senators Bernard, McPhedran, Mitchell, Mégie and Pate for their contributions to this discussion thus far and to commend them for what they have put on the table for us to think about.

As I was preparing my remarks today, I couldn’t help but remember Senator Mégie’s retelling of how anti-Black racism plays out in the lives of people. I am not Black, but I am Brown, and I too have experienced racism — institutional racism, for instance — when in the first 10 years of my life in Canada, Canadian work experience kept getting put on the table. But somehow I think — at least I feel — it is always the expressions of racism that are personal that hurt the most; for instance, the many times I have been mistaken as a customer service employee in a grocery store where I am shopping simply because of the colour of my skin. “You’re Brown; you must work here.”

But in listening to Senator Mégie, I now feel that what I have experienced are mere pinpricks. No one follows me around in a store. I am not frightened that my children will get pulled over when driving. I am not subject to discriminatory practices such as carding. So I conclude that just as there are different seasons, there are also different degrees and shades of racism.

And lest we think that racism is particularly present in one race or one people or one country, let me also point out that I think it is sadly more universal than that. In India, the country where I grew up, we were all Brown but shades of Brown. So some northern Indians will look down on some southern Indians because they are a darker shade of Brown.

I want to focus primarily on the language that contributes to anti-Black racism, because language is a reflection of our values; it shapes our ideas and gives voice and expression to how we see sameness or difference. Language, therefore, becomes a powerful expression of racism, even more so when we use it casually, with no intention to offend or harm.

A cursory look at some of the terminology reveals that the word “black” is associated with negatives and pejoratives. Because language is learned either as a mother tongue or other, these terms become part of our vocabulary, and we therefore become part of the casual racism that is implicit in them.

Let me give you a few examples and use their dictionary definition as I do so.

A blacklist is defined as a “list of people or groups of people regarded as unacceptable or untrustworthy and often marked down for punishment or exclusion.”

Blackmail is to “threaten or manipulate their feelings to force them to do something.”

A black mark is a “note or record of a person’s misdemeanour or discreditable action.”

A blackguard is a “thoroughly unprincipled person.”

To blackball someone is to ostracize them socially or commercially.

To be the black sheep in your family is to be a member who is “regarded as a disgrace to it.”

I think we all know what Black Monday meant on that date in the 1980s. It referred to the financial crash in stock markets and the loss of prosperity for many.

I could go on and on — black book, black heart, black magic, black spot — but I want to think about this expression in other languages, and because we are a bilingual country, I looked at French. Sadly, to my great disappointment and disadvantage, I speak no French. It is my firm intention one day to be able to stand up and at least make a statement in reasonable French.

I reached out to my francophone colleagues for help with this, whether racism is embedded indeed with the association of the word “black” only in English or does it exist in French as well?

Senator Cormier told me that there is an expression, I think it’s regional, that is trou noir, or black hole, which has a whole different meaning in parts of the country where there is seasonal unemployment. Trou noir, or black hole, is referred to the time between when you lose your job and when you gain your benefits.

(1440)

The French version of “black sheep” is “brebis galeuse,” which roughly translates into “a flock of scabs.”

I grant that there are nouns with “black” in them that are not negative: blacksmith, blackberry, blackjack — I don’t know about blackjack. But what is surprising is that there are no words with “black” that are expressly positive.

African-American studies professor Dr. Vernon McClean has a list of terms under “blackness,” derived from the latest edition of the thesaurus. There are 120 synonyms, of which over half are distinctly unfavourable to Black people.

I hope honourable senators don’t think this is my attempt to instill into our discussion some kind of language police or political correctness. Rather, I think this is an acknowledgment of our own individual and, hopefully, collective power and ability to influence the discourse in this chamber and beyond.

As we have learned in recent times from our neighbours south of our border, words matter. When leaders incite hatred or promote stereotypes and falsehoods based on race, ethnicity or cultural differences, it inspires others to pursue those same ends to an even greater or violent extreme, and the same must be said for the everyday language that often goes unchecked.

To again quote Vernon McClean:

. . . language not only expresses ideas and concepts, but also actually shapes thought.

. . . while we may not be in a position to change the English language, we can . . . change our usage of the language.

. . . we can avoid using words that degrade black people. We can make a conscious effort to use adjectives that reflect a progressive perspective, as opposed to a distortion of the black experience.

Or, as an anthropology professor has so aptly said, we must see race through a lens of language, and language through a lens of race.

Thank you very much.